Introduction

StreetMesh is an open source framework for spatially organizing the Web, building upon open standards, existing protocols and tools, and guided by human-centered design.

This project establishes the Protocol for StreetMesh: a set of rules that allow people, machines, and spaces to coexist on the Web with the same fluidity and orientation we experience in the physical world. StreetMesh brings spatial reasoning, decentralized identity, and embodied interaction into one coherent system.

StreetMesh is built upon open standards—like HTTP, DIDs, OAuth, and ATProtocol—and invites developers, designers, educators, and builders to use familiar tools—like HTML and JavaScript—to compose digital places that are designed to feel present, navigable, and personal.

In StreetMesh, a webpage isn't just graphics on a screen. It's a room you can walk through. A dashboard isn't just data. It's a mission control center. A social feed isn't just endless scroll. It's a gathering place you can step into or out of.

StreetMesh provides the scaffolding to make a spatial web possible—and to make it feel right:

- Creating a storefront that feels like an inviting destination for customers

- Teaching eager learners inside a dynamic, navigable learning environment

- Hosting a town hall where everyone can be seen, heard, and respected

- Building AI companions who show up with purpose and don't pretend to be human

StreetMesh is the Web, restructured for humans and machines to build a shared world—not just exchange information.

To better understand where we're going, let's start at the beginning.

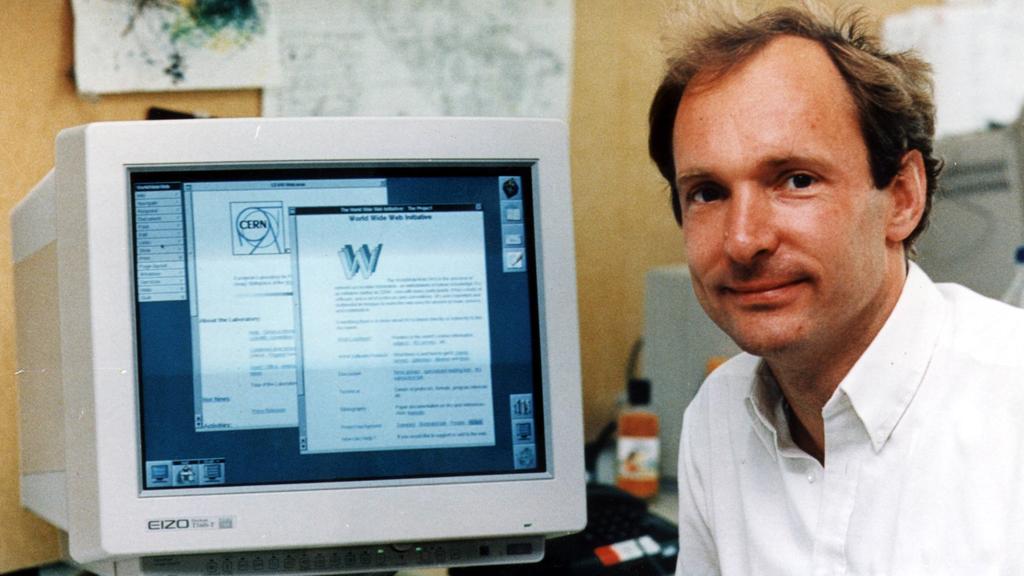

The First Web: Information

The World Wide Web was born in 1989, and went public in 1993. A really smart English guy named Tim Berners-Lee invented a bunch of technologies—including HTML, URLs, and HTTP—and gave birth to web pages: a simple, robust, visual communication toolset that unlocked an unprecedented era of hyper-connection and rapid communication.

While Tim Berners-Lee created the first Web browser, it was a company called Netscape that moved the Web out of the academic space and into so-called "personal computing."

In 1995, in a bid to make the Web and webpages more interactive, Netscape created the scripting language JavaScript. Less than one year later, another new technology called Cascading Style Sheets would create separation between content and layout, allowing the web to become beautiful while still being accessible.

Every webpage on every website that you've ever interacted with, from Amazon to Wikipedia, was built upon these base technologies. If you're a web developer, every framework you've ever used was built upon this platform: jQuery, Vue.js, React, AngularJS, Bootstrap, Tailwind, and so many others.

This was Web 1.0. The browser-makers fought wars over standardization and market dominance, but still, it was a simpler time.

The Second Web: Participation

In 1999, Darcy DiNucci coined the term "Web 2.0":

"The Web we know now, which loads into a browser window in essentially static screenfuls, is only an embryo of the Web to come. The first glimmerings of Web 2.0 are beginning to appear, and we are just starting to see how that embryo might develop. The Web will be understood not as screenfuls of text and graphics but as a transport mechanism, the ether through which interactivity happens. It will [...] appear on your computer screen, [...] on your TV set [...] your car dashboard [...] your cell phone [...] hand-held game machines [...] maybe even your microwave oven."

This era of the Web is marked by the rise of participation and collaboration, much of which happens in the social web, with much of that activity occuring on specially made software called "apps" that run on pocket-sized computers that for some (reasonable) reason we still call "phones." While unlike web browsers in form, apps' functionality rely heavily on the same base technologies that powered the first Web, especially HTTP.

Some apps are even made using web presentation technologies—HTML, CSS and JavaScript—and are wrapped to run like native apps on our mobile devices. There's never been a more interesting or democratized time to be a software creator.

Web 2.0 gave birth to the dot-com startup, which bubbled and then burst even as it unleashed household names we still have today, like Amazon and eBay. That early volatility created a new economic space that today contains enormously valuable companies that serve their customers exclusively through the Web—not only by ecommerce, but also through entire software tools (called SaaS) like Slack, Google Workspace, and Zoom.

The social web is a grand experiment we are running on humanity. Much of the social web is funded by targeted advertising: a new form of marketing made possible by the data we all feed into the Web just by using the tools and services that live there. Our attention has a cash value, and so the social web has been designed to extract as much of our attention as possible. Experts agree this is a big problem, and we still haven't figured out how to fix it.

And so this is Web 2.0, still alive today. The whole world got online, created new ways of exchanging goods and services, subjected our minds and our societies to systemic forces we are still working to understand, and gave rise to a new class: the tech-billionare-enterpreneur.

The Third Web: Decentralization

Web 1.0 was a vision for a world of information that was interlinked and could be explored by both humans and machines. That vision continues today, even as the landscape has evolved dramatically.

Web 2.0 is a platform, built upon the successes of Web 1.0, enabling companies and people to contribute content, communicate in real-time, and transact business. It is alive and well.

Web3 would be a reorganization of the systems and ownership stake that power the Web, dramatically reducing the power of central authorities on the way to eliminating them.

Depending upon who you ask, Web3 might be a fairy tale, a marketing "buzz" word, or it might just be the next great vision for how to connect humanity and its information.

For the purposes of this exploration of the Web and for paving the way to a spatial web and StreetMesh, Web3 is best thought of as a mission: to value decentralization because decentralized systems are resilient, but to value interoperability and portability more highly, because interoperable systems that offer data portability will attract more people.

did:web

Decentralized identifiers (DIDs) are unique names (in fact, they are a kind of Uniform Resource Identifier or URI) that enable the identity of a person, place, or thing (or data, or entity of some sort) to be verified without relying on a centralized registry.

These are all valid DIDs:

did:street:collegeman.streetmesh.com

did:web:aaroncollegeman.com

did:plc:jflaisf993jfkdjlskdfj993jf

Notice how some of them look like website addresses? Website addresses, which are registered using DNS systems (which are decentralized systems), can function as DIDs. In this way, a DID can be used to access a DID document using traditional Web 1.0 technologies.

What is a DID document? A DID document can contain many things, including something called public keys. Public keys, when part of a public/private key pair, can be used to authenticate (unlock) and subsequently authorize transactions of data or value between two people, or companies, or systems.

In this way, what's old (URLs) becomes new again (DIDs). Since I can use a URL as a DID, and because I can host an HTML file behind a URL on a simple HTTP server—including the computer sitting in the corner of my basement office—my ability to prove who I am to any other system is dependent only on an agreement on how to go about doing the verification.

By embracing DIDs for portable identity, we look forward to the fully decentralized Web, in which everyone uses personal digital wallets to own their identities, while still maximizing Web 1.0 technologies like DNS to advance toward the next versions of the Web.

OAuth

In Web 2.0, the era of apps and social login buttons, a pattern emerged: users wanted the convenience of reusing their identity across platforms without surrendering their passwords to every third-party site. This is the problem OAuth was created to solve.

OAuth (Open Authorization) is a protocol that allows users to grant limited access to their resources on one site (say, Google or Facebook) to another site (say, Spotify or Airbnb), without having to give away their password. Think of it as a valet key for your identity—one that can start the engine, but not open the glovebox.

When you click "Log in with Google," you're not handing over your Gmail password. Instead, OAuth allows Google to vouch for you—confirming that you are who you say you are—without disclosing any sensitive credentials. It's a handshake that says, "Yes, I trust this person," backed by public/private keys and time-limited permissions.

OAuth became a foundational part of Web 2.0's Identity layer, allowing services to interoperate smoothly while preserving a semblance of privacy and control. But OAuth has always required a trusted central authority—like Google or Facebook—to act as the broker.

And therein lies the rub.

As we look toward Web3 we see a need to decouple authentication and identity from centralized silos. OAuth paved the way, but now we need a new model. One where users are the authority, not the platforms. That's where DIDs and verifiable credentials pick up the torch. Instead of relying on a single provider to issue access tokens, Web3 architectures imagine a world where each person holds their own keys—literally—and can present cryptographic proof of who they are, on their own terms.

Still, OAuth is not going away anytime soon. In fact, many of the Web3 identity systems are designed to interoperate with OAuth, recognizing its wide adoption and real-world utility. OAuth isn't dead—it's just growing up, finding new friends in new protocols, helping us bridge between the present and the future.

OAuth was the glue that held the early participatory web together. The next chapter is about portability of identity across space, platforms, and even realities—and OAuth's legacy lives on in the APIs and protocols that power that transition.

ATProtocol

If OAuth was about access and delegation in Web 2.0, the Authenticated Transfer Protocol (ATProtocol) is about portability and permanence in Web3.

Built by the team behind Bluesky, ATProtocol is an attempt to rewire the social layer of the internet—to separate the identity you are from the apps you use. In today's world, your identity and content are typically locked inside the walled garden where you created them. Your Twitter handle belongs to Twitter. Your Instagram followers? Also Instagram. If you want to move to a new app, you start over.

ATProtocol says: That's ridiculous.

At its core, ATProtocol is a federated social protocol. It gives users portable identities, composable data, and algorithmic choice. That means:

- You can own your handle (as a DID)

- You can take your followers and posts with you to another platform that uses the same protocol

- You can choose the algorithm that shapes your feed, instead of letting a black-box model decide what you see

This isn't some utopian fantasy. It's already happening.

ATProtocol uses DIDs (like did:plc:abc123) for user identities, so you're not tied to a single company's infrastructure. Your identity is decentralized from the start. It uses lexicons (a structured way to define schemas) to make data interoperable across apps. And it supports repo sync, so your data is mirrored across multiple servers—you're never dependent on one node or provider.

In this world, app developers focus on UI and experience, not lock-in. Users have agency. Content creators don't lose everything when a platform goes dark. And trust is earned, not inherited from a corporate brand.

Most importantly, ATProtocol is designed to coexist with existing web standards. That means it doesn't burn down the Web—it builds alongside it.

Blockchain

No discussion of Web3 could be complete without mentioning Blockchain. Here, we introduce Blockchain with one important caveat: we don't believe the spatial web is dependent upon Blockchain—to create such a dependency is a willful act of design, one that introduces enormous complexity without yielding tangible benefits.

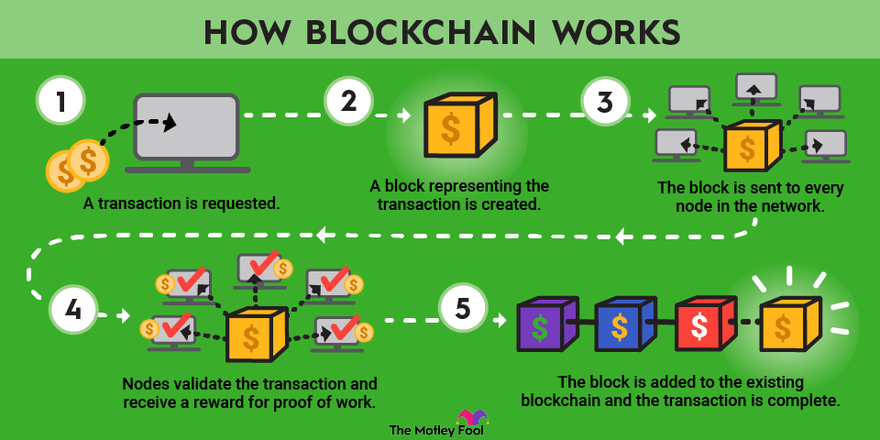

Evangelists of Web3 believe that Blockchain is to Web3 what HTTP was to Web 1.0 and 2.0: it's the base technology that makes all the rest possible. The promise of Blockchain is a future in which there are no longer any central authorities needed to verify the authenticity of a contract. But how?

Blockchains are a kind of distributed ledger: any time there's a transaction of data or value in the history of a blockchain, that transaction becomes a record in a chain of records—that chain is the ledger. Tampering with any one of the chains in the ledger invalidates the entire ledger.

Since it is only possible to modify a blockchain by agreeing to a specific crytographic process and having the keys with which to make an authorized change, the process is self-securing. This self-securing according to rules that all participants have agreed to follow is how we eliminate needing a central authority to validate transactions or keep their history.

No central authorities means no banks needed to authorize the transaction of money, no multinational corporations needed to authorize the transaction of goods and services, and no central governing body to authorize changing the rules. It's all in the Maths!

There are many applications of this technology, with the most common (and least interesting) being Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. Other implementations of blockchain like Ethereum can be used as currency but are also used to implement other applications of blockchain technology, like Smart Contracts, Decentralized Identities, and Decentralized Autonomous Organizations.

The world we live in is built upon centralized authority, so the world resists blockchain solutions. Blockchain technologies are inherently less efficient than databases, requiring lots of power for the ever increasing computational cost of adding chains to a blocks, for any purpose. The inefficiency combined with the resistance creates interference, and interference slows adoption.

These are fighting words, of course. There are many who have invested heavily in a blockchain based web. We wish them well, but we don't believe the next phase of the web should be dependent upon this technology. A strong commitment to interoperability outmodes blockchain.

So the solutions to problems of decentralized identity and authentication—DIDs and OAuth—are a hedge. These solutions are forward compatible with blockchain and a fully decentralized Web while being backward compatible with the centralized systems we have today.

The Next Web: Posthumanization

Web 1.0 was about information.

Web 2.0 is about participation.

Web3 is about decentralization.

What comes next? Some argue that the next Web is the Posthuman Web.

Now, before you recoil at the term—let's clear something up. Posthumanization does not mean the end of humanity. It doesn't mean a world where humans are obsolete, or where cold machines replace warm people. That's dystopian science fiction. In truth, Posthumanization is about collaboration—a new partnership between people and machines, each bringing their strengths to the table.

(In fact, ChatGPT played a strong role in finishing the document you've been reading here.)

Humans are storytellers. Meaning-makers. Pattern-seekers. Machines, especially those powered by artificial intelligence, are phenomenal at absorbing vast datasets, running complex models, and responding instantly. Together, we're starting to create in ways that neither could do alone.

The Next Web, the Posthuman Web, will be co-authored. It will be designed, written, coded, and organized not just by humans using tools, but by humans conversing with intelligent systems. Not just clicking or tapping, but collaborating. That might look like:

- Designers sketching rough ideas that AIs bring to life with code.

- Writers co-developing characters and plotlines with a language model.

- Educators tailoring real-time learning paths based on each student's progress and preferences.

- Communities governed by algorithms they understand and choose—rather than ones imposed by distant platforms.

In this world, identity doesn't just mean who you are online, but also how you work with machines. You'll have intelligent agents that speak on your behalf, assist in decision-making, or even act as extensions of your personality. These agents won't replace you—they'll amplify you.

Posthumanization isn't about losing our humanity. It's about expanding it—freeing us from the mechanical parts of work and creativity so we can focus more on meaning, relationships, and care. It invites us to be more human, not less.

And it's already underway. Every time you talk to an AI assistant, train a model with your own data, or use automation to manage complexity—you're participating in the early stages of posthuman collaboration.

The question is not whether machines will be part of the next web. They already are.

The real question is: How will we design that relationship?

Large Language Models

At a high level, a Large Language Model or LLM is a kind of AI system trained to understand and generate human language. These models consume vast amounts of text—books, articles, conversations, code—and then learn to predict what words (or symbols) are most likely to come next. It's the same basic skill we humans use when finishing each other's sentences, only scaled up to billions of parameters and entire internets of data.

You can think of an LLM as a kind of linguistic interface—a bridge between human intention and machine execution. And that bridge goes both ways. Need to summarize a legal contract? Translate a poem? Write a database query? Brainstorm marketing copy? Draft a letter to your landlord in the voice of Jane Austen? LLMs can do that. They’re not just tools—they’re collaborators, especially when paired with your own knowledge, goals, and judgment.

LLMs aren’t perfect. They can hallucinate facts, reflect biases from their training data, and speak with confidence even when they're wrong. But here's the key insight for the Posthuman Web: they don’t need to be perfect to be useful. They just need to be interactive, transparent, and trainable. In a Posthuman Web, LLMs show up in powerful new roles:

- As conversational agents—not to impersonate people, but to extend human capacity

- As tutors, adapting learning content to individual learner's pace and style

- As teammates, co-authoring content, writing code, or prototyping ideas in real time

- As interfaces, helping users interact with complex systems using plain language instead of forms

In a Posthuman Web, LLMs become more than chatbots. They become trusted companions, workflow accelerators, and context-aware interpreters of the digital world.

The Spatial Web

So, how will we design the relationship between humans, machines, and the information they create?

We'll design it the way humans have always made sense of the world: through space.

The Spatial Web is a vision of the Web that feels like being somewhere. Not in the metaphysical, VR-goggles-required sense (though sometimes that too), but in the way space is experienced by the body and remembered by the brain: as orientation, proximity, movement, and context.

We're spatial creatures. Our memories live in places. We remember stories by where we were when we heard them, we navigate complex ideas by organizing them in mind-palaces, studios, dashboards, and sticky-note walls. The Spatial Web leverages this deeply human intelligence—the kind that developed long before we learned to read—to create digital experiences that feel coherent, memorable, and alive.

This web is not flat. It's layered, inhabitable, and structured around relationships, not just links. It builds on everything that came before, asking a new question:

What if information didn't just appear on screens? What if it existed somewhere? What if the web felt like something?

That something is presence.

Let's imagine a few moments in this Spatial Web:

You're shopping, but it doesn't feel like scrolling a page of thumbnails. It feels like walking into a market. You pass by curated stalls, chat with an AI shopkeeper who knows your size and your style but doesn't pretend to be a person. You discover a designer from Dakar, another from Tokyo. You turn a corner and find a sale bin, just like you would in a physical store—but it's tuned to your preferences, not just your clicks.

You attend an event—a public meeting, a lecture, a jam session—and it feels like actually being there. You don't just watch a livestream; you move through the space, overhear side conversations, and walk up to someone to say hi. When someone shares a link or a chart, it doesn't interrupt—it appears next to you, ready to explore when you're ready.

Your AI assistant appears as a presence, maybe a floating point of light or a talking fox—but never pretending to be human. You know it's a machine. It knows it too. But you talk naturally, gesture when you speak, and it responds like a partner who understands your goals and helps you think clearly, not just faster.

You're learning something new, and the knowledge isn't locked in PDFs. It surrounds you—interactive models, simulations, live feedback, conversations that branch based on your curiosity. You don't memorize facts. You inhabit ideas.

You go to work. Not in a cubicle, not in a chat window, but in a workshop full of collaborators. Some are in London, others in Nairobi. A few are agents you've trained to do research, draft proposals, or run tests. There's a bulletin board with active projects, a map of your team's progress, and a quiet corner where you go when you need to think.

In the Spatial Web, the boundaries between tools, teams, and ideas dissolve into a kind of intelligent architecture—where people, machines, and meaning exist in shared context.

The Spatial Web is a true metaverse. It is not a gimmick or a buzzword. It is an evolution of how we interact with the digital world. It recognizes that embodiment matters, even online. That physical metaphors—rooms, proximity, paths, points of view—aren't nostalgic relics, but cognitive technologies that help us think better, together.

And most importantly: this future is not locked into blockchain. It's compatible with Web3 but not dependent on it. It's open. It's layered. It's built on standards we already have and protocols we're still discovering. The Spatial Web is not a platform you buy into. It's a pattern you participate in.

There is life to be lived here. Educations to be earned. Work to be done. Worlds to be built. People to meet. Stories to remember.

The Spatial Web is not a dream. It's a direction.

WebXR

WebXR stands for Web Extended Reality—a set of APIs that bring virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to the Web browser. No special app stores. No proprietary platforms. Just the open web, extended into three dimensions.

Imagine walking through a digital art gallery, placing a 3D model on your desk for inspection, or attending a virtual classroom that exists not as a video stream, but as a room you can move around in. WebXR makes these kinds of experiences not only possible, but accessible—to anyone with a web browser and a device that supports it.

Want to try it? Check out the Examples page in the @react-three/xr project. If you have a Meta Quest device, you can use this link() to open the Examples in the web browser on your Quest.

This is what makes WebXR special. Unlike most XR platforms that live behind corporate gates, WebXR is part of the open standards movement. It's built to be interoperable, portable, and linkable—meaning your immersive experience can live at a URL, just like a traditional webpage. It's the Web we know, just deeper.

In the context of the Spatial Web, WebXR plays a crucial role:

- It enables embodied interaction, letting users move, look, gesture, and even walk through digital content

- It supports shared spaces, where people (and AI agents) can meet, talk, and collaborate in ways that feel physical—even when remote

- It makes the Web not just a canvas for displaying data, but a place you can inhabit

WebXR is still young. It's evolving. But the promise is big: a truly spatial, interoperable layer for the Web that doesn't depend on walled gardens or proprietary app stores. It brings the kind of interactivity we associate with games or simulations into everyday tools, learning environments, workplaces, and social spaces.

Summary

In this introduction, we introduced StreetMesh: an open-source architecture for building a spatial Web. It's a framework for crafting spatial, embodied, and human-centered digital experiences that work with today's Web—and are ready for tomorrow's.

We explored how the Web has evolved across three major phases:

- Web 1.0, the era of information—built on open standards and static pages.

- Web 2.0, the era of participation—powered by social platforms, apps, and targeted experiences.

- Web3, or Web 3.0, the era of decentralization—focused on user control, identity, and distributed trust.

We also began imagining what comes next:

- A Posthuman Web, where people and machines collaborate—not in competition, but in partnership

- And the Spatial Web, where information isn't just presented but experienced, using space, memory, and presence as organizing principles

We reviewed foundational technologies like HTTP, HTML, JavaScript, OAuth, DIDs, ATProtocol, and WebXR, each playing a role in this new landscape of the spatial Web.

Read Next: Design

In Design, we'll reorient our thinking away from technology to the experience of a spatial Web.